2025

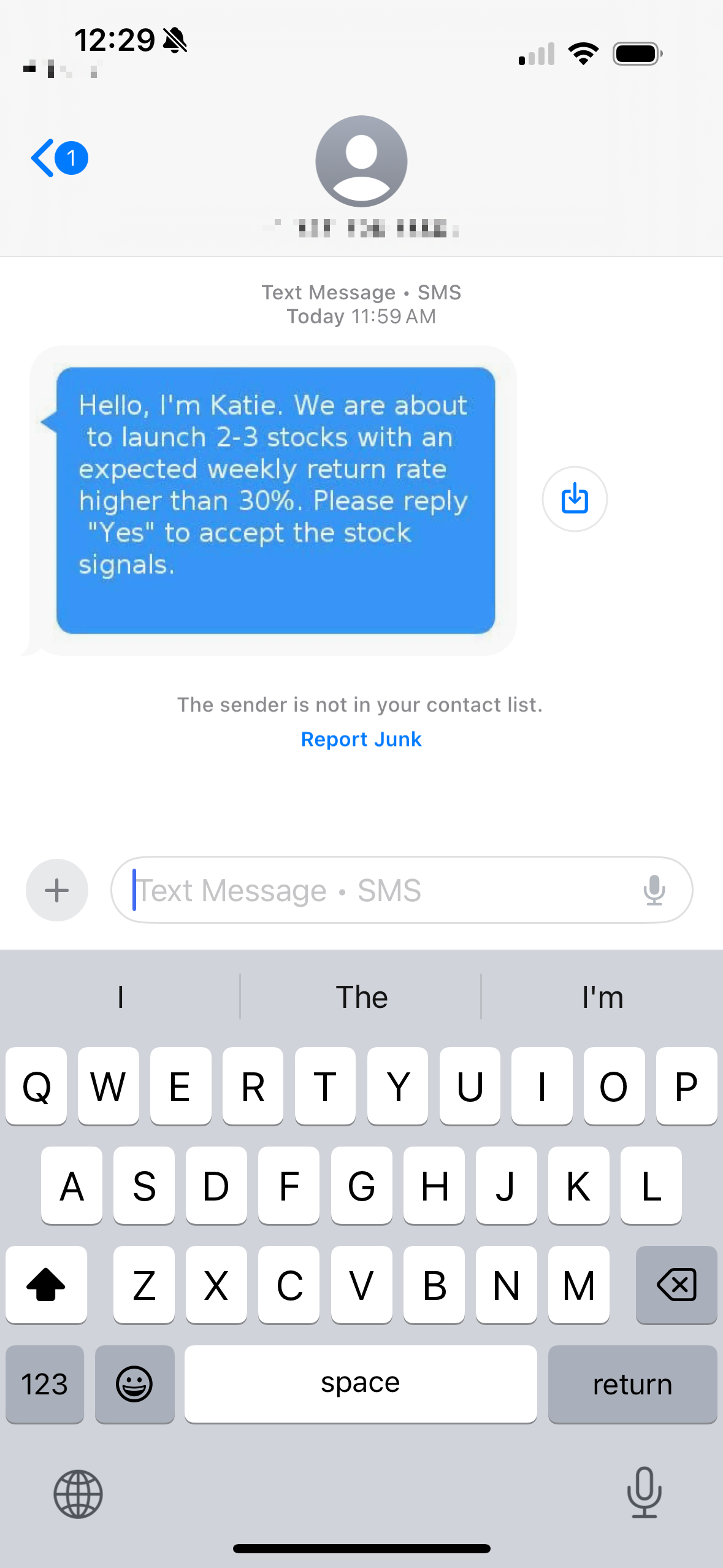

This one was new to me: this scammer sent me a “fake” iMessage, trying to hide the fact that it’s an SMS.

Cities and Ambition (2008)

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the relationship between my environment and my personal growth lately. Small ways, like how people perceive your choice of city–a founder told me they think of New York as a “lifestyle city” for example, at least if you’re in tech. Big ways, like who your neighbors will be–a lot of my friends have talked about moving there not just for fun, but because it’s where their customers are. Of course, pg was writing about this in 2008 and SF and New York are very different cities now than they were back then, but not so different that his framework isn’t useful.

Windsurf gets raided by Google

From TechCrunch:

In a shocking twist, Google DeepMind is now hiring Windsurf CEO Varun Mohan, co-founder Douglas Chen, and some of the startup’s top researchers. A Google spokesperson confirmed the hiring of Windsurf’s leaders in a statement to TechCrunch.

I know a lot of the Windsurf folks, so this news makes me both a little excited for them but also a little scared. Time (or leaks) will tell if this $2.4 billion acqui-hire plays out well for the team.

Update: I’m late to this. From The Information via Twitter:

- Employees with vested shares will receive cash – Employees who joined less than 12 months ago are not vested and won’t get payouts under current terms – Windsurf negotiated to keep $100M+ on its balance sheet; company will shift focus to enterprise customers

- Remaining company will now be employee owned

This is similar in structure to the Scale deal, employees who joined later on not only get less, they get next to nothing. I’m still lost as to what this exit means. Was it that Windsurf ran out of options? That Microsoft accessing their IP was too big of a no-go?

Despite the proliferation of AI agents in B2B, it’s still very difficult to actually make or use them as a consumer. I don’t really want to use MCP locally to power all of this, so I’ve just been throwing relay.app at everything to do structured research and interpretation.

Warp is now an “Agentic Development Environment”

If you don’t know Warp, it’s a pretty nice terminal app that I’ve been using for a number of years; I mostly use it because it lets me copy entire command responses and other quality of life stuff like that. I really enjoy it and have recommended to everyone I talk to.

One of the things it’s never gotten me to do though is pay for it; I mostly just expect my terminal to be my terminal. I’ve seen a couple of angles they’ve taken: the enterprise route with some of their collaborative team features was the first one, and as AI started up everywhere, trying to directly integrate LLMs into your terminal.

It certainly sounds like they’re trying to go well down the latter route with their 2.0 launch:

The products on the market today…bolt agents onto code editors through chat panels and bury them in CLI apps. What’s needed is a product native to the agentic workflow; one primarily designed for prompting, multi-threading, agent management, and human-agent collaboration across real-world codebases and infrastructure. […] With Warp 2.0, the ADE [“Agentic Development Environment”], this is all fixed: it’s amazing at coding and really any development task you can think of. You tell it what to build, how to build it, and it gets to work, looping you in when needed.

To be honest though, I’m not seeing the vision. I mean, I like the new design of the terminal, but what’s going to compel me to use their AI inputs over, say, Claude Code? (I’m also not gonna really comment on the SWE-bench scores because I don’t really find them to represent how much they actually help me.) I’m seeing some possible answers in the post, but none are really interesting to me yet.

One contender is multitasking (“multithreading”). Cursor/Windsurf still don’t really support having multiple chats yet, which annoys me. But far from being “buried” in a CLI app, claude can just be run in multiple tabs to the exact same effect. And every (local) solution so far is always working off the same copy of your code. So sure, like the demo shows, you can be writing some code in one tab, doing code review in another, and reading logs in a third. But it’s still awkwardly aware that I can’t test two bugs at the same time, or really, multitask anything that requires running code locally.1

The knowledge angle is similarly lacking for me. At anywhere I’ve worked, I already have Notion, Slack, Google Drive, as well as AGENTS.md, CLAUDE.md and Cursor rules. It feels redundant to be creating another central team store. I think shared MCP could be interesting, but right now I’d be too scared of accidental credential leakage, so maybe one day that’ll be interesting.

So really what it’s doing is just giving me another coding wrapper. I don’t think that’s a bad thing! I think there are many fantastic wrappers out there, but I really don’t think it’s fair to call the status quo “bolted on,” “buried,” or inferior compared to the vision they describe. There’s really just two things that would compel me to use it over my current spate of AI coding tools short of unique models: a better harness (which is a tough, tough hill to climb in a world with CLI coding tools built in tight connection with the underlying models), or a radically better way to manage and steer the agents. I’m excited to see if they can deliver on these.

-

As I was writing this post, a few friends have noted git-worktree as a potential solution to allow multitasking here, and have done so with Claude Code. This is a great partial solution, and you can get as far as multitasking test running. But after that it still gets really awkward, and this makes it even stranger that Warp doesn’t use this in their demo video! ↩︎

Biome v2 now lints types

This is now a real alternative to eslint.

Underusing Snapshot Testing

I’m a huge fan of snapshot testing, especially in JavaScript/TypeScript where types often lie, ane especially in backend. This article was a good reminder to me why I think it’s such a powerful tool in the arsenal.

Remeda

If you’re greenfielding a JavaScript application, I can’t recommend enough starting with Remeda. The main reason here is that unlike lodash, Remeda is composable and functional, but unlike something like Ramda, you aren’t forced to use data last all the time. In the same breath:

const items = [1, 2, 3];

const doubled = R.map(items, (x) => x * 2);

const doubleSquared = R.pipe(

R.map((x) => x * 2),

R.map((x) => x ** 2),

);

It makes functional programming practical in the semi-functional style that works really well in modern TypeScript.

obsidian-omnisearch

Omnisearch is a search engine that “just works”. It always instantly shows you the most relevant results, thanks to its smart weighting algorithm.

I’ve been taking more notes lately on pen and paper, partially because I got a very nice Memosyne notepad and fountain pen from Japan, but also because it’s easier for me to not feel distracted when I’m not using a keyboard.

But I also want to be able to index and search my notes. But I also don’t want to move off Obsidian (all of the AI note taking apps have yet to sway me, despite the Tana invitation collecting dust in my inbox). So I’m trying to find stuff that OCRs properly, or can use an LVM to clean it up for me.

I’ll post back about this if it’s lifechanging, but probably not. Let’s be real, it’ll probably just sit in my configuraiton for a while and be banally useful.

Egoless Engineering

Perfectly reasonable people thought that maybe we should put more of a wall between designers and the css source code. […] But instead a miracle happened. There was an inspired person who decided to do the opposite. They just yolo’d giving the designer the deploy keys. […] We spent our free time building everything we needed to in terms of monitoring, test suites, et cetera to make that safe for them to do. Everyone rejoiced and got shit done. Nothing bad happened.

When this talk was first shared with me, my mind was blown because everything I had ever heard about building an organization, was that we need people to respect their lanes and learn to communicate with each other. I don’t think that value is wrong (talking cross-functionally is important in almost any organization), but this talk blurred the lines for me between what is good communication, and what is building fiefdoms.

Make your discipline more accessible This should be part of your job!

I will say, the challenges here are really, really underemphasized. (Not to say it’s not worth it, of course, but that there’s more to it.) If I don’t have the right tooling needed, making a code change, ensuring it’s safe, and deploying it to production is barely safe for an engineer, now imagine someone without the skills to debug if the flow fails half the time.

Sometimes the walls come up because people want to perpetuate those little stupid fiefdoms, but sometimes it’s just because it’s the easiest thing to do, everything is on fire, and you don’t have the time.

(The perfect retort to that, which I believe, is if you set your team and processes up to be accessible from the start, it’s pretty cheap to maintain it, and people will even help you point out failures far sooner. Looked at this way, fiefdoms are organizational debt that can be paid down easily at the start, but not much later.)

Gleam, coming from Erlang

Most of my professional experience has been in Node, but it’s clear to me that despite working fantastically in practice, there’s so many limits to the event loop that make it really hard to write performant code correctly. I’d love an environment that combines the expressiveness of TypeScript/JavaScript with the concurrency of something like BEAM, and I’d love it to be mainstream.

A Mostly Sane Guide to Root Cause Analysis

It finally happened. A Friday afternoon not long before a huge launch, somebody deployed a last-minute change that crashed the database, and you were on-call. It took a harrowing three hours to roll back the code, find the backups and run the restore, but by sheer force of will you were finally able to get it all back up.

But now the real work begins. Customers are mad, leadership is anxious about something like this happening again, and as the on-call, all eyes are on you to write a post-mortem to explain what happened and how this will never happen again.

So today, we’re gonna do a root cause analysis, the heart and engine of the post-mortem discussion.

Why we root cause

At its heart, a root cause analysis is the process of taking an incident and determining what systemically caused it. In a root cause analysis, it’s not enough to be able to explain why it happened, you have to be able to explain why it was only a matter of time that this issue was going to occur. It’s making the best of whatever downtime, or lost data, or customer pain you’ve endured, and an attempt for a team learn as much as possible from it, and if you’re lucky, find things you can do to prevent incidents like this from happening again.

From the top

The way that I’ve always been brought up to do root cause analysis is with a bastardized version of the Five Whys technique. It’s far from perfect, but it works well I think because it’s a simple and flexible way to think about root cause analysis.

Here’s our v0 of the root cause analysis from the story above:

- The production database crashed.

- Why? An engineer pushed code that added an expensive query that exhausted the database’s memory.

To start, this answer shouldn’t feel satisfying. Human error contributes to almost every incident, but for that exact reason, pinning the blame on a person doing something dumb isn’t productive.

We can strengthen this analysis by focusing on the crash itself to start, and shrinking the size of the logical leaps:

- The production database crashed.

- Why? The production database ran out of memory.

- Why? Query XYZ exhausted the production database’s memory.

- Why? Executing the query required storing millions of records in memory.

- Why did we have this query? The query is a key part of our new reports tool.

- Why does it store so much? We didn’t optimize the query before deploying it.

- Why? Executing the query required storing millions of records in memory.

- Why? Query XYZ exhausted the production database’s memory.

- Why? The production database ran out of memory.

While the analysis (so far) doesn’t come to a different conclusion from our v0, it’s getting more robust, and we can better justify our assessment. Let’s extend our line of questioning a couple more steps:

- The production database crashed.

- Why? The production database ran out of memory.

- Why? Query XYZ exhausted the production database’s memory.

- Why? Executing the query required storing millions of records in memory.

- Why did we have this query? We used the query to build a new report.

- Why does it store so much? We didn’t optimize the query before deploying it.

- Why? We don’t have any tools to test our code against data at scale.

- Why wasn’t this caught in code review? The reviewer did not have SQL performance expertise.

- Why didn’t someone else review? The engineers with the strongest SQL expertise were out of office.

- Why didn’t this reviewer have expertise? We don’t have documented best practices on common pitfalls in SQL.

- Why? Executing the query required storing millions of records in memory.

- Why? Query XYZ exhausted the production database’s memory.

- Why? The production database ran out of memory.

Unlike a more “standard” Five Whys analysis you’ll see, I really like this branching format. Instead of looking for just the “root” cause I can pursue each line of causation independently. This helps me because I can start pursuing multiple suggestions for a post-mortem, and the contributing factors matter.

What makes a cause, a “root” cause?

Some of the branches ended at the fifth Why, and some ended earlier. It really doesn’t matter whether you stop at five. What matters is that at the end of each branch, you’ve reached what you’d consider to be the root cause.

This is easier said than done. When researching for this post, I found most definitions of “root cause” to be incredibly vague and hand-wavy. Rather than philosophizing about the nature of cause and effect in our reality, I’ll instead take a more functional view on what a root cause is: in a world without the root cause, the incident could not have occurred, 95% of the time.

There’s a few general questions I like to use to feel out if I’m satisfied with a root cause:

- Was it one person’s silly mistake? If one mistake amounts to an incident, it’s not the root cause. Look deeper at the systems (technical or organizational) that allowed or enabled that person make that mistake instead.

- Does the effect feel inevitable given the cause? In the above example, without having any way to test a query’s performance at scale, it was only a matter of time before the database melted down over a bad query. If it feels like something was bound to happen given the cause you’re presenting, you’re probably onto something.

- Was it a deliberate decision? Deliberate policy or architecture decisions are useful as root causes because they dictate how our day-to-day, smaller decisions are made. Not requiring code review or picking the wrong approach for building a feature are both good examples of this; if I pick a system design that makes it hard to write performant code, less performant code will be written. Fixing these key decisions has massive downstream effects.

The hardest part of this exercise will always be knowing when to stop. Given enough iterations, you can almost always root cause any incident to “we had to ship this thing quickly and didn’t budget enough time,” for example. Back to the functional viewpoint of things, you can generally stop at the point your analysis is giving you good ideas of what to fix or improve. It’s a delicate balance between trying to be intellectually honest while also acknowledging that you’re here to fix problems, not write philosophy.

What’s Next

You brought your root cause analysis to the incident review, and it was met with a hearty round of applause. (I kid. I’ve never seen a post-mortem get that emotional.) Now you’re looking at the root causes, and let the team brainstorm ways to mitigate them:

- The problematic query was used for a minor feature in the reports tool.

- The reviewer did not have SQL performance expertise.

- We don’t have any tools to test our code against data at scale.

One engineer offered to go back to product and see if there was a less intensive way to build a similar report, while another person offered to do a small class on SQL performance. Since you already had a small staging environment with synthetic data, you offered to beef up the amount of synthetic data in staging to make it easier to test reports at scale before it takes down production. A fantastic start and another incident in the books.

There’s a lot of ways to root cause, and to be honest, the methods I’ve seen in software engineering would not be considered root cause analysis in other fields. What I described here, of course, is one method that I’ve seen work in software engineering, and presents a balance between rigorous thinking and constant demands on time. Unlike any kind of analysis a flight investigator, say, would do, this is barely an analysis, but in software, these kinds of things are written in a couple days, not several months. It’s really about extracting as much learning in as little time as possible.

Always learning, ✌️

Some Further Reading

The importance of psychological safety in incident management

Incident.io’s basic treatise on how to conduct incident management with psychological safety, and why it matters. I touched on the concept here, but this one goes in a bit more depth.

Inhumanity of Root Cause Analysis

This is a cynical, but nevertheless very informed opinion of the way root cause analysis is used in organizations.

Pagerduty’s main guide on running an incident analysis. By default, Pagerduty’s guides are what I use when trying to think about incident management from the ground up.